Content Purgatory is real, and in my lived experience, my cherished work used to end up there frequently because of approvals. (It does this less now for reasons I'll get to at the end!)

Projects have this nasty way of sitting finished but unpublished because somewhere along the chain of command, someone's priority wasn't in line. Someone had other things to do. They got sick. There were no contingencies.

Alignment issues like these have only become more common and more workflow-breaking since the majority of content is now either prepared specifically for, or partially, for social media. Management teams still, in 2026, have a lot of reticence about posting on social because of blow-back, brand perception, and other hazardous happenings. They do it because they feel that they must, but rarely with calm nerves.

Meanwhile, campaigns are ready to go but feel stalled. Teams follow up politely, then less politely, then escalate, all while the status work itself doesn’t change.

AI has not made this better. It may have improved grammar and given everyone a false sense of security about quality, but it has also given leaders and approvers the notion that it can be used for quality assurance and alignment - dangerous concepts with a system that still requires careful babysitting.

The usual explanation is that leaders are busy, overloaded, and your Instagram post isn't always their top priority. Or ever.

That is true, but it doesn’t really explain anything. Plenty of busy leaders approve some things quickly and others painfully slowly. It can feel really random.

Approvals don’t slow down because leaders are slow. They slow down because approvals are being used as a substitute for decisions that were never properly made earlier.

What an Approval Actually Represents

An approval is not a neutral workflow step.

It is a moment of accountability.

When a leader approves something, they are implicitly attaching their name to it. If the decision turns out badly, they are the one who will be asked why it was allowed to happen. That means every approval request forces a decision-maker to pause and assess risk.

They need to understand what they are approving in context. They need to know how this fits with previous priorities, what trade-offs it implies, and what consequences they are accepting by saying yes. If that picture is unclear, slowing down is the safest possible response.

From the outside, this looks like procrastination. From the inside, it is entirely rational.

Why Approvals Become Bottlenecks

Most approvals arrive on the desks of those responsible without enough structure to answer the real questions behind them.

A leader is sent a document, a draft, or a link, often weeks after the original discussion that supposedly set direction. The approval request assumes shared memory and shared understanding that simply no longer exists. The leader is expected to reconstruct why this work exists, how important it is compared to everything else on their plate, and what will happen if they let it proceed.

That reconstruction takes time and attention, the two scarcest resources in any senior role. When those resources aren’t available, approvals get delayed, bounced back with vague feedback, or reopened for discussion long after teams thought decisions were settled.

This is why “leaders are busy” is not a sufficient explanation. Leaders are always busy. Approvals slow down when they demand fresh judgment instead of confirming an already-bounded decision.

Why More Context Rarely Solves the Problem

When approvals slow down, teams often respond by adding more explanation. This could be longer briefs, more background slides, or additional documentation meant to “make things clearer.”

In practice, this often makes the situation worse.

More information does not reduce the risk of slow approvals. It increases it. A longer document signals that there is more to understand, more nuance to miss, and more surface area for something to go wrong. Instead of narrowing the decision, it expands it.

What slows approvals is not a lack of clarity, but the size of the decision being asked. As long as an approval requires a leader to make a broad, open-ended judgment, it will compete poorly with everything else demanding their attention.

What Actually Makes Approvals Faster

Approvals speed up when they stop asking leaders to re-evaluate everything from scratch.

The fastest approvals are the ones where the leader does not have to decide whether something is good in general, aligned in principle, or wise in the abstract. They are asked something much smaller: whether this work deviates from what was already agreed, and whether that deviation is acceptable.

This shift sounds subtle, but it is decisive. A narrow decision is far easier to make than a holistic one, especially under time pressure.

Similarly, approvals move faster when they are no longer the default safety net for all work!

In many organizations, approvals exist simply because no one ever explicitly decided that certain types of work don’t require them. Over time, this leads to everything flowing upward, even when the risk is minimal and the cost of delay is high.

Reducing approval bottlenecks often has less to do with improving workflows and more to do with clarifying where leaders actually need to be involved and where they don’t.

Designing for Reality, Not Best Intentions

Another reason approvals slow down is that they are often designed for an ideal version of leadership attention. They assume careful reading, full context, and thoughtful reflection.

They assume that your supervisor is an editor. That they are even qualified to judge the work accurately.

This is among the biggest frustrations for creators who feel they have to defend their work to someone who may not understand its function or its connection to a campaign.

Real approvals happen between meetings, on mobile devices, late at night, or while switching between unrelated problems.

Work that acknowledges this reality moves faster. Work that assumes ideal conditions does not.

Approvals that are concise, explicit about risk, and clear about what happens if no response is given are far more likely to be handled promptly than those that rely on goodwill or thoroughness.

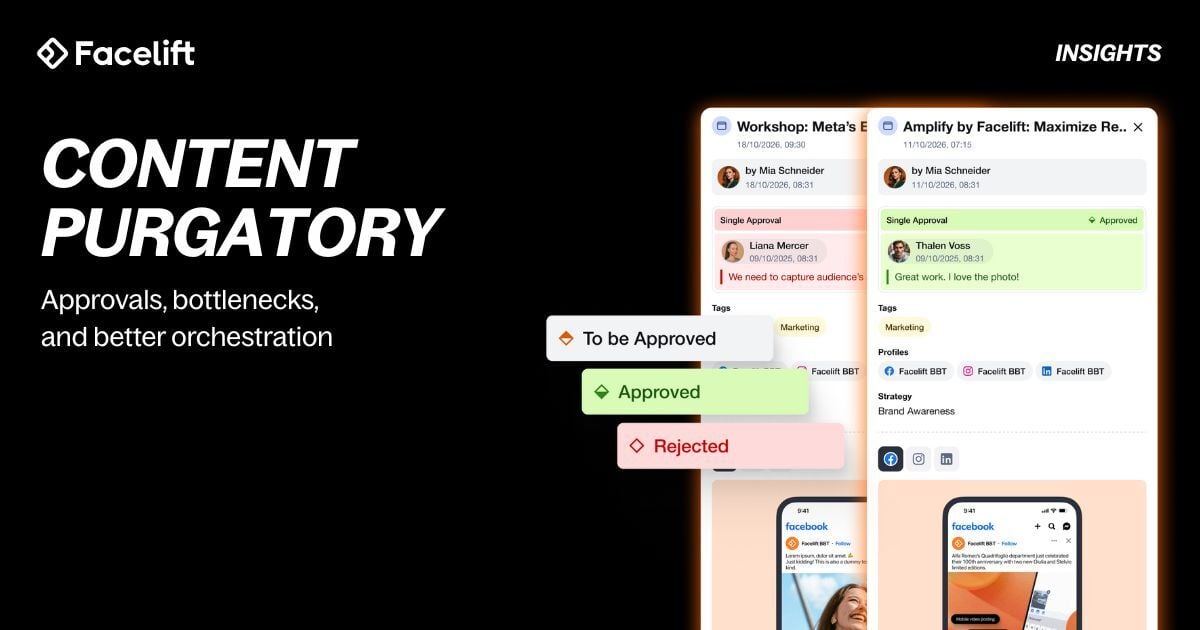

Approval Purgatory in Communication Orchestration

Communication Orchestration offers a way to help teams collaborate at scale and reduce some of the day-to-day friction that comes with the handover process.

Approvals are only one part of a multifaceted issue that comes with the transition of content from person to person, or team to team.

Part of what orchestration offers is the ability to integrate teams from throughout the organization to provide input or create their own content under a single, shared communication hierarchy.

This is intended to create alignment between content and business objectives.

One way that this addresses approvals is by bringing personnel who need to do approvals or offer input to a project early to prevent late-stage risk perception. If the project feels like a team project from the start, it works to everyone's advantage and can shorten the approval process.

You can read more about Communication Orchestration here.

This is how my workflow has improved with regard to approvals, since Facelift adopted Communication Orchestration.

I currently work with Facelift's communication hierarchy, which is just a tree of communication and content points that connects everything I create to our company's vision and mission (or our Pinnacle Statements, as they are called).

I am able to communicate content projects with colleagues at a greatly enhanced rate, and have more autonomy over what I write and what I ship than I ever have before.

Facelift just launched a major new product update, our Spring Edition update, which dropped a bunch of new workflow improvements, including upgrades to the way approvals are orchestrated. Take a look for more!

What This All Comes Down To

The approval system is overloaded.

Methodologies like Communication Orchestration can help with this, but they cannot solve this overload alone.

Approvals slow workflows when they are used to absorb uncertainty, resolve misalignment, and compensate for decisions that were never fully owned earlier in the process. No amount of tooling, documentation, or new methodologies can fix this.

Companies that want approvals to move faster have to do less at the approval stage, not more. That means narrowing decision scope, reducing how often approvals are required, and accepting that not every risk can be managed from the top.

It also means an orchestrated approach that grants more autonomy to creators, social media managers, and others.

Until that happens, approvals will continue to feel slow, and frustration will run close to the surface.